Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

_and_Mouche.jpg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25)

Built in Milford Haven, Wales in 1810 and commissioned on the 22nd July 1811 under Captain Philip Browne she played a part in the Napoleonic Wars

The 18th-century Royal Navy stood as an indomitable force, securing Great Britain's supremacy on the seas. HMS Hermes, one of the Royal Navy's distinguished ships, played a pivotal role in this era of maritime dominance. However, the success of the Royal Navy was not without its challenges, as it faced the scarcity of sailors, harsh living conditions, and the controversial practice of press ganging. This article delves into the remarkable story of HMS Hermes and sheds light on the extraordinary achievements of the British naval forces during this period.

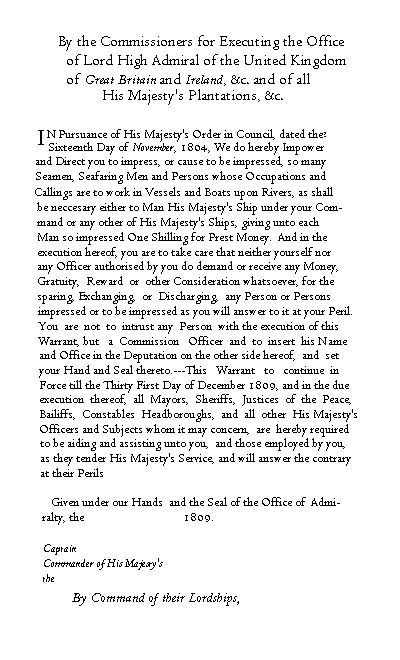

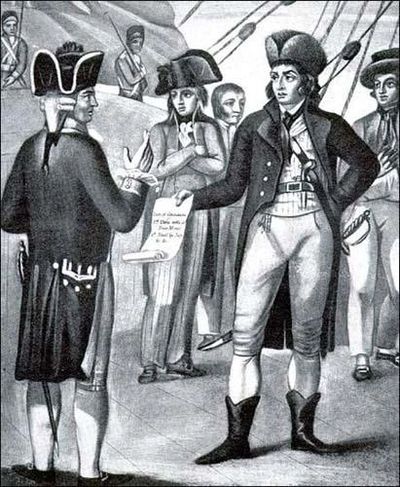

During a time when men were urgently needed to defend their country, the British Parliament resorted to press ganging, a practice that involved forcibly conscripting men into naval service. Mainly targeted at the lower classes, press ganging employed tactics of entrapment, fraud, and even violence to fill the ranks. Families often remained oblivious to the fate of their loved ones, who were snatched from towns and countryside. Desperate for sailors, ships at sea were even raided, leaving them short of crew to return to port. Despite the controversial nature of press ganging, it became an unfortunate necessity to bolster the Royal Navy's manpower. In 1793 there were 15,000 men in the Royal Navy, by 1813 there were 150,000.

Life aboard naval vessels in the 18th century was far from comfortable. Ships were designed primarily for warfare rather than the well-being of their crews. Even merchant vessels carried arms and engaged in maritime warfare. Officers and sailors endured cramped quarters, spending extended periods at sea. The living conditions were harsh, with little privacy or personal space. Yet, despite these hardships, the crews of HMS Hermes and other British warships demonstrated incredible resilience and adaptability in the face of adversity.

The Royal Navy operated under the Articles of War, which outlined the regulations and expectations for the behavior of the crew. These rules were read at the commissioning of a ship and repeated monthly thereafter. In the 18th century, there were 35 articles, with the final one granting captains discretionary powers to punish disciplinary infractions not specifically named in the previous articles. While this gave the captain authority, it also necessitated fair judgment and responsible leadership to maintain order and discipline within the crew.

In spite of the challenges faced by the Royal Navy, it emerged as the most effective fighting force of its time. The crews of British warships, including HMS Hermes, were renowned for their well-organized, well-drilled, and cohesive teams. Driven by ambition, mutual respect, and a shared identity, these sailors worked tirelessly towards a common cause. They excelled in handling sails and firing cannons more rapidly than their adversaries. Moreover, the British prioritized cleanliness, leading to a reduction in disease outbreaks and subsequent losses. Although exceptions existed, such as bad officers, unruly men, and ill-fated ships, they were rare in comparison to the overall effectiveness of the Royal Navy.

HMS Hermes, like many other ships of the Royal Navy during the 18th century, represents the unwavering spirit and remarkable achievements of the British naval forces. Despite the controversies surrounding press ganging and the challenging living conditions at sea, the crews of these vessels demonstrated unwavering dedication, professionalism, and resilience. Their ability to work as a cohesive unit and their commitment to excellence enabled the Royal Navy to win great battles and emerge victorious in numerous wars. The legacy of HMS Hermes and its counterparts serves as a testament to the power of teamwork and the indomitable spirit of those who fought for their country on the high seas.

Born on September 16th, 1772, Captain Philip Browne was a renowned figure in the British Royal Navy during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His remarkable career was marked by bravery, exceptional leadership, and a relentless pursuit of victory on the high seas. Despite his tragic early loss, Captain Browne left an indelible mark on British naval history.

Philip Browne was the son of the late Captain Philip Browne, R.N., who tragically lost his life in the defence of Savannah in 1779 at the age of 38. Perhaps inspired by his father's sacrifice, Browne's own naval journey began at a tender age. Joining the service as a midshipman at the age of 15, his exceptional talent and dedication propelled him through the ranks.

By the time Browne turned 21, he had already attained the rank of Lieutenant, a testament to his competence and commitment to the navy. His meteoric rise continued, and in 1810, at the age of 38, he achieved the esteemed rank of Captain. However, it was not just his rapid ascension that set Captain Browne apart; it was his extraordinary achievements on the seas.

Captain Browne's naval career was studded with unparalleled success, and his service aboard various ships showcased his prowess and tactical brilliance. Notably, his attachment to the Swan, Vixen, Plover, and Hermes would forever be remembered for their remarkable feats. During his time commanding these vessels, Captain Browne achieved astounding victories.

In his career, Captain Browne captured a total of 11 privateers, which collectively boasted an impressive 114 guns and a crew of 744 men. Furthermore, he successfully apprehended and detained 37 merchantmen, laden with valuable cargoes worth a staggering 300,000 pounds. Unfortunately, due to the laws of the time, these spoils were claimed as droits of Admiralty.

Captain Browne's achievements extended beyond capturing enemy vessels and confiscating their wealth. He also played a pivotal role in protecting British interests and ensuring the safety of British seamen. His endeavors included the rescue of 200 British seamen from captivity, the reclamation of 13 valuable British trading-vessels, and the capture of 868 French prisoners.

Additionally, Captain Browne's dedication to curbing smuggling activities earned him further accolades. He seized 20 smuggling-vessels, which generated a considerable profit of 47,214 pounds, 11 shillings, and 10 pence for the Crown. His unwavering commitment to upholding British law and protecting national interests was evident in these achievements.

One of the notable milestones in Captain Browne's career was his commissioning of the HMS Hermes on July 22nd, 1811. As captain of this illustrious vessel, he continued to exemplify exceptional leadership and demonstrated the unwavering spirit of the British navy.

Captain Philip Browne's naval career was marked by audacity, strategic brilliance, and unwavering devotion to duty. His exceptional accomplishments not only bolstered British naval power but also secured the nation's maritime interests during a crucial period in history. His relentless pursuit of victory and commitment to protecting British seamen and trade routes made him a revered figure among his contemporaries.

Tragically, Captain Browne's brilliant career was cut short. However, his legacy lives on, immortalized in the annals of British naval history. His extraordinary achievements serve as an enduring testament to the indomitable spirit of those who serve their country at sea. Captain Philip Browne's name shall forever be etched among the most celebrated heroes of the Royal Navy.

HMS Belle Poule, the Gipsy, and HMS Hermes, by Thomas Butterworth

Armed with 2 x 9 pounder guns and 18 x 32 pounder carronades she was a 20 gun, Hermes class, sixth rate, flush decked post ship. Post ships were smaller than a frigate but at that time ships with between 20 and 26 guns had to have a Captain command the vessel rather than a Lieutenant. During the 17th and 18th Centuries ships were rated, initially on ships complement, later on gun complement hence Hermes being of the 6th rate.

With a design complement of 135 crew she set sail. The first ship she captured was an American vessel with stores for the fleet around Brest, next were two ships from New York and Baltimore with tobacco and ivory on board.

On the 24th September 1811 she was sailing close to Cape la Neve when she spotted and recaptured the Prussian brig, Anna Maria, however, the privateer managed to escape due to the high winds and the closeness of the French coast. Anna Maria had been bound for London from Lisbon.

The winds caused Hermes to go "off station" and prevented Browne from reaching St Helens so Captain Browne bore to Dungerness. Off Beachy Head she discovered a large French Lugger amongst several English vessels, one of which she had already captured for a prize. Had she not have been discovered by Hermes she would have surely taken the rest..

Hermes gave chase and after 2 hours the privateer having sustained some damage and had several men injured struck at Hermes. Hermes slowed allowing the violence of the strong winds to break her maintop sail yard in the slings and her fore sail split. The privateer took the opportunity immediately to escape on the opposite tack. Hermes managed to turn and cram on all sail., despite a 2 mile lead on the weather bow Hermes managed to catch up. Despite the weather, Browne was determined not to let the Lugger escape and decided to run alongside her but the Lugger crossed Hermes hawse and a heavy sea caused Hermes to run over the top of her, sinking her.

Of the 51 men on board the Lugger only 12 were saved. Fortunately none of the men on the English "prize" had been taken on board the Lugger previously, in fact 10 men from the Lugger were on board the "prize" which had escaped to France during the chase taking the Luggers men with them.

The Lugger turned out to be the Mouche of Boulogne commanded by M. Gageux, and mounting 14 carriage guns, 12 and 6-pounders.

Hermes captured the American Brig, Flora on the 11th February 1812 and went on to capture the American brig, Tigress on the 26th..

The following day was the start of a 3 day chase in the mid Atlantic after the letter of marque schooner, Gypsy with HMS Belle Poule. This 300 ton (bm) vessel, armed with 12 x 18 pounder carronades and an 18 pounder gun mounted on a pivot was laden with a cargo worth £50,000 when she was on her way from New York City to Bordeaux. Gypsy surrendered twice to Hermes and both times got away before Belle Poule caught her.

In the winter of 1812, Hermes and the 36 gun 5th rate Frigate, Phoebe were sent to the Azores under the command of Captain Francis Austen (brother of novelist Jane Austen) commander of the 74 gun third rate HMS Elephant.

An 11 hour chase covering over 100 miles on the 27th December led to the capture of the American private schooner, Sword Fish of Gloucester by Hermes and Elephant. John Evans was Master of her crew of 82 men. She had sailed out of Boston 16 days earlier and had made no captures. Despite being only 4 miles ahead at the start, she lightened her load by throwing 10 of her 12 x 6 pounder carronades over the side.

HMS Elephant

In 1813 Hermes escorted a convoy of merchant ships to South America. On the 13th April, whilst proceeding from Cork the convoy encountered the brig, Recompense which was not a part of the convoy. The master of the Recompense fell foul of the convoy by the most wilful mismanagement of his ship which he also forced upon the Hermes which was in imminent danger of being lost.

Captain Browne ordered the Master of the Recompense to anchor and warned him against the lubberly mode in which he was proceeding. The Masters reply was to call Captain Browne "a damned white faced rascal" and that if they were ashore he would thrash him. He refused to anchor and again ran the Recompense foul of the Hermes. At the time Captain Browne was too pre-occupied with the dangerous situation of his own ship.

Three weeks later, off Madeira, the Recompense again came very close to Hermes and Lieutenant John Kent of the Hermes offered to bring the Master of the Recompense on board with his papers. The Master, once on board, behaved with even greater insolence until Captain Browne took off his coat, remembering the previous threat and told the Master to make good on his promise. The Master, in order to avoid a fight, laid down on the deck of his own accord. He also refused to meet the Captain ashore privately. He told some Marines to pick the Master up from the deck and Lieutenant John Kent to see him back to his ship.

First Lieutenant Charles Letch who had recently been brought before a court marshal by Captain Browne for gross misconduct and oppression of inferior officers for which he was convicted, brought charges against Captain Browne.

On the 30th March 1814 a court marshal assembled in Plymouth to hear the seven charges brought against Captain Browne which he had only heard of himself 48 hours previously.

Although one of the charges was abandoned by the prosecution and most of the others disproved by witnesses the court judged that the charges as a whole to be proved and Captain Browne to be dismissed from the service. An eminent counsel immediately announced that the decision cannot be legal as each charge should have been addressed on its own accord. Once the sentence of the Naval court marshal was promulgated the prisoner was excluded from all redress.

Nevertheless Captain Browne presented a memorial to the Admiralty with how now he had the time to prepare a defence he had official documents to refute the accusations. Referring to himself as the memorialist below is an extract:

“That the facts of the case were not fairly before the court-martial, is most evident, from the circumstances well known to the Commander-in-chief at Plymouth, and every member of the court, that your memorialist was utterly incapable of making any sufficient defence to the charges, not only from severe indisposition of body and mind, but from his being in perfect ignorance of the existence of such an accusation till 48 hours before he was a prisoner in court. The charges were not transmitted through him, nor intimated to him, as is customary. He had no time to summon many witnesses whom he might have called for his justification, or to consult any friends or advisers as to his defence; but through au excess of reliance on his own innocence, disdained to delay the investigation a single hour; and thus he suffered heavy charges to pass under trial, without taking the means of repelling them, which common prudence rendered necessary

“Your Lordships will be unable to discover the cause of the virulent malice, which so obviously pervades the whole of the charges, without a short explanation of the motives and character of the prosecutor. Lieutenant Charles Letch had sailed several years with your memorialist, and had enjoyed his confidence in a very great degree; Lieutenant John Kent had also been two years in the Hermes. Both had lived in the utmost harmony with your memorialist until a few weeks before the arrival of the Hermes, when these officers, especially the first, presuming on the friendship and protection with which your memorialiist had long distinguished them, fell into such relaxation of discipline, and into such habits of oppression towards the inferior officers, as made it absolutely necessary at last (however painful) for your memorialist to interfere; which they resented by the many instances of faction, animosity, quarrelling, and disrespect, which are fully detailed in the recent court-martial on Lieutenant Letch, and in many other papers before your Lordships, to which your memoralist refers; and if further evidence be necessary, that the charges originated in private pique and malice, and by no means for the good of the service, it would be found in this consideration, that the facts alluded to in the first and second charges, had occurred twelve and six months respectively before the Lieutenants ever thought of making them the subject of prosecution, although it is proved in the minutes that there were several opportunities at Rio de Janeiro of bringing your memorialist to trial, where witnesses and parties were on the spot, of whose evidence your memorialist was unfortunately deprived.

“The first charge is in substance,– ‘That on the 25th April, 1813, in sight of Madeira, your memorialist sent for the master of the merchant-brig Recompense, on board the Hermes, and in the presence of the officers and ship’s company abused him and challenged him to fight, took off his coat, and squared at him in an attitude, and aimed or made a blow at him; and the master then lying down on the deck of his own accord, that your memorialist ordered some marines to take off his coat, and oblige to him stand up, which attempt the master resisting, the marines tore his coat: and that your memorialist then challenged him to go on shore to fight at Madeira, by which conduct your memorialist was alleged to have violated the 23d and 33d articles of war.’

“The 23d article of war recites, ‘that if any person in the fleet shall quarrel or fight with any other person in the fleet, or use reproachful or provoking speeches or gestures tending to make any quarrel or disturbance, he shall upon being convicted thereof, suffer such punishment,’ &c. &c. &c.

“The 33d article of war alleged to be violated, recites, ‘that if any flag-officer, captain, commander, or lieutenant, belonging to the fleet, shall be convicted of behaving in a scandalous, infamous, cruel, or oppressive manner, unbecoming the character of an officer, he shall be dismissed his Majesty’s service.’

“Such are the crimes of which your memoralist is accused, and such is the law which he is stated to have infringed. The simple facts of the case, in as far as they are in evidence before your Lordships on the minutes, are these:–

“On the 3d April (three weeks before the time of the transaction), your memorialist, proceeding from Cork, in his Majesty’s ship the Hermes, with a convoy, happened to encounter the brig Recompense (not of the convoy), the master of which, by the most wilful mismanagement of his ship, ran foul of one of the convoy, which he also forced on board of his Majesty’s ship, which was in imminent danger of being lost thereby. It is sworn, that the master could have prevented the accident of entangling the ships if he chose, but that the Hermes could not possibly avoid them. That your memorialist, in the alarm which he felt for the safety of the ship, called vehemently to the master of the brig Recompense to let go his anchor, and warned him against the lubberly mode in which he was proceeding. That the master not only refused to desist from his misconduct, but actually forced the other vessel foul of the Hermes; and in reply to your memorialist’s desire to let go his anchor, it is sworn, even by the prosecutor’s own evidence, that the said master, without any provocation, in presence of all the officers and crew of the Hermes, called him a damned white-faced rascal, and said that if he had him on shore he would thrash him. At this time, from the dangerous situation of the Hermes, and the urgent necessity of putting his orders in execution, your memorialist had no possibility of communication with the ship-master. That three weeks after this outrage, when in sight of the island of Madeira, the same vessel came close to the Hermes, and Lieutenant Kent pointed the master out as the aggressor, and offered to bring him on board the Hermes with his papers for examination; to which your memorialist consented. That the master, on coming on board, behaved even then with great insolence and effrontery; and that your memorialist, excessively irritated by his demeanour, and by the insolent threat of personal chastisement, by which the ship-master had so recently outraged his feelings, asked him what he meant by such abuse, and if he could now make good his threat, and face him as a man, and that he, the memorialist, would take no advantage, although in his own ship – and then threw off his coat for the purpose: that the ship-master, to avoid fighting, lay down on the deck of his own accord; and your memorialist declaring he would not strike him when down, ordered some marines who stood by to raise him up: but his clothes were not torn; he received no abuse except being called a damned Irishman, nor was the smallest violence offered to him; neither did the memorialist ever attempt to strike him. That your memorialist then asked the master if he would meet him on shore singly to execute his threat; which he refusing, your memorialist put on his coat and left him, desiring Lieutenant Kent to see him on board, to press any man that he might find liable, but gave him especial orders not to distress him in consequence of which none were impressed. That Lieutenant Letch, the prosecutor, remarked at the time, that the captain was too warm, but that the master of the Recompense deserved worse treatment than what he had received; and that he, as well as Lieutenant Kent, repeatedly afterwards approved of the circumstance.

“Such is every particular of evidence on the transaction in question, whether for or against your memorialist, which the minutes of the court martial afford; and he has the more carefully selected them, because, with the exception of the present charge, your Lordships will find, there is not a shadow of blame to be imputed to your memorialist, that can arise, by any possibility, out of the other charges, which it will hereafter be shewn, were utterly false, malicious, and vexatious.

“With respect to the articles of war which your memorialist’s conduct on this occasion is alleged to have violated; he humbly begs to observe to your Lordships, that the 23d article is wholly inapplicable to the case, as this article prohibits one person belonging to his Majesty’s fleet from fighting with, or provoking, any other person belonging to the same fleet; whereas, in the present instance, only one of the parties is in his Majesty’s service; moreover, that it is an article seldom or never acted upon.

“But the 33d article is, in fact, that alone which is contemplated to affect your memorialist’s case; on which he has also humbly to observe, that he is informed, that the penal acts of parliament ought to be strictly interpreted according to the letter, and not to be in any case strained by inference against the accused. That, in this instance, the legal question is not, whether the transaction was in itself generally that which is said to be unbecoming the character of an officer and a gentleman; but, whether it was scandalous, infamous, cruel, oppressive, or fraudulent; and by being which, but not otherwise, it would be unbecoming the character of a gentleman; cruelty, oppression, and fraud, is here quite out of the question: and your memorialist most confidently submits to your Lordships’ superior wisdom, to your candour and justice, that the quality of the transaction did not deserve the character of scandalous and infamous, in the sense intended by the article of war; and he submits fully to your Lordships, that there is not in all the annals of martial law, in the navy, an instance or precedent, of scandal or infamy being attached by the sentence of any court martial to such a transaction as the present.

“But while your memorialist pleads not guilty to the charge in a legal sense – his own feelings as an officer and a gentleman, condemn him for the intemperance of passion, which hurried him into so improper an excess. He fully admits the indecorous and bad example of his conduct. He deplores with the utmost contrition, that unhappy violence of temper, which, acted upon by sudden and irresistible provocation, has led him, when threatened with actual personal outrage, to forget that he was an officer, and to remember only that he was a man, and by no means a coward, or one that would shrink from the personal violence of any man under heaven. To your Lordships, as men of high personal courage, he appeals for indulgence to this instance of human frailty. To such of your Lordships as are officers, and have been in his situation, he puts his case, and implores you to consider candidly the insolent abuse frequently offered by the low-bred masters of merchantmen, whose violence there is no law to punish, and whose vulgar excesses there are no feelings, except the fear of personal chastisement, to restrain. He asks your Lordships, whether allowance may not be made for a captain of one of his Majesty’s ships having his passions worked up almost to frenzy on such an occasion as that; where his ship, and the lives of his men, are wilfully put in imminent danger, as well as his character as a seaman; and when he is told, in presence of all his crew, that but for their protection the aggressor would have thrashed him! – The candour of your Lordships will not fail to make allowance for him: and your memorialist trusts, that when he shews that, with the above exception, he is entirely guiltless of every other charge, your lordships will deem, that he has, by the disgrace he has suffered in dismissal, been already most cruelly punished for the venial offence which he committed, and that the sentence of the court martial is severe beyond all precedent, and ought to be mitigated.” * * * * * * * *

In consequence of this memorial, the minutes of the court-martial were laid before Sir William Garrow and Sir Samuel Shepherd, the law officers of the Crown, who unhesitatingly declared that the proceedings of the court were informal and irregular, and that there was nothing in the evidence which could warrant the sentence passed against Captain Browne, who was at length restored to his former rank, but not until the attention of Parliament had been called to the subject by his noble friend, the Earl of Egremont, April 20, 1816.

In April of 1814, Captain, The Honourable William Percy took command of Hermes.

On 5 August Hermes and Carron sailed from the Havana and arrived at the mouth of the Apalachicola river on the 13th. They landed a detachment of marines under the command of brevet Lieutenant Colonel. Nicolls on Vincent Island then proceeded with him to Prospect Bluff where they learnt that brevet Captain Woodbine had gone to Pensacola on board Sophie to assist a party of friendly Indians which the Americans had driven into Spanish territory. Captain Woodbine sent a hired vessel to Vincent Island to bring them arms and ammunition from the dump at the Bluff.

Hermes left the Apalachicola on 21 August and arrived at Pensacola two days later, falling in with Sophie off the bar. The Spanish Governor requested that he should disembark the detachment and arms since he was threatened by an attack from the Americans, and this was immediately complied with. The Fort San Miguel was put in the hands of Lieutenant Colonel Nicholls and the colours of both countries hoisted.

Captain Lockyer of Sophie was directed to proceed to Barataria to see if the freebooters there would co-operate with British forces, and to offer them lands in the colonies.

Lafitte, their commander, whilst pretending to consider the British proposals, forwarded them to the Governor of Louisiana.

Childers joined them on 6 September from New Providence with more arms and ammunition for the Indians and flour for the squadron. In order to communicate with the Choctawa tribe, supposedly friendly, Captain Percy decided that he would have to take possession of Mobile.

By capturing Fort Bowyer on Mobile Point he would be able to stop the trade of Louisiana and starve Mobile into surrender.

The fort appeared to be a low wood battery of little strength, mounting by some accounts, no more than fourteen guns of small calibre, and by others, as few as six. There was supposed to be sufficient depth of water for the ships to anchor within pistol-shot. Carron was detained to assist and Lieutenant Colonel Nicholls offered to command a party of about 60 marines and 130 Indians.

Hermes, Childers, Carron and Sophie, which they met off the bar, sailed on the 11th. and the following day they landed the Nicholls party and a howitzer about 9 miles to the eastward of Fort Bowyer.

Contrary winds prevented them passing the bar until the 15th., during which time the Americans strengthened their defences. They passed over at ten past three in the afternoon in the following line of battle: Hermes, Sophie Carron, Childers. The fort started firing at sixteen minutes past four and Hermes replied with a broadside, then anchored fore and aft, at half past. Sophie did the same ten minutes later but since her timbers were rotten her carronades drew the bolts or turned over when they were fired. Lack of wind and a strong tide prevented the other two ships from coming up and they were forced to anchor too far off to be of use.

When her bow spring was shot away Hermes swung round head to the fort and grounded. Only one carronade and the small arms in the tops could reply to the raking fire the enemy poured in. Captain Percy managed to bring the larboard battery to bear by cutting the small bower and using a spanker to catch what wind there was to turn the ship. At ten past six, having made no impression on the fort with the few larboard guns that could fire, and having lost a considerable number of men, he cut all cables and tried to drop clear of the fort using the strong tide.

Hermes, with all her rigging shot away, was unmanageable and grounded with her stern to the fort.

Captain Lockyer and Spencer came on board and agreed that it was impracticable to attempt to storm the fort so, while Sophie's boats under Lieutenant Peter Maingy, 1st. Lieutenant of Hermes, took off the wounded and other men, Captain Percy and Lieutenant Alfred Matthews performed the painful duty of setting fire to Hermes. The rest of the squadron then anchored about one and a half miles from the fort and, at 10 o'clock they saw HERMES blow up.

HERMES lost 17 killed including Mr Richard C. PYNE, master; Mr B. HEWLETT, master's mate and Mr G. THOMPSON, boatswain. Twenty-five were wounded, including five mortally so.

Fort Bowyer eventually fell in February 1815 and contained three long 32-pounders, eight 24's, six 12's, five 9's, one brass 4-pounder, one mortar and one howitzer, with a garrison of 375 officers and men.

Captain Percy faced a court martial on board Cydnus off Cat Island on 18 January 1815. The court found that the attack was justified and he was acquitted of all blame for the loss of the ship.